Editor's note: Milwaukee Art Museum provided source material to Resource Library for the following article or essay. If you have questions or comments regarding the source material, please contact the Milwaukee Art Museum directly through either this phone number or web address:

The Arts and Crafts Movement in Europe and America, 1880-1920: Design for the Modern World

May 19 - September 5, 2005

(above: Table lamp, 19024.

From the Susan Lawrence Dana House, Springfield, Illinois. Designed by Frank

Lloyd Wright (United States, 18671959). Made by Linden Glass Co., Chicago,

Illinois. Leaded glass, bronze, brass, and zinc, Base: 20 1/2 x 12 x 8 7/8

inches (52 x 30.5 x 22.5 cm); shade diameter: 29 inches (73.7 cm). LACMA,

gift of Max Palevsky M.2000.180.44ab)

The groundbreaking

exhibition The Arts and Crafts Movement in Europe and America, 1880-1920:

Design for the Modern World, places a crucial phase of decorative arts history into an international context

for the first time. On view at the Milwaukee Art Museum May 19 - September

5, the exhibition showcases more than 300 Arts and Crafts objects from the

United States and throughout Europe -- including furniture, ceramics, metalwork,

textiles, and works on paper - borrowed from 75 institutions and private

collections.

a crucial phase of decorative arts history into an international context

for the first time. On view at the Milwaukee Art Museum May 19 - September

5, the exhibition showcases more than 300 Arts and Crafts objects from the

United States and throughout Europe -- including furniture, ceramics, metalwork,

textiles, and works on paper - borrowed from 75 institutions and private

collections.

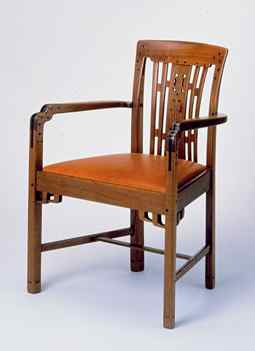

"We're excited to showcase an international view of the Arts and Crafts movement, already popular locally," said Glenn Adamson, curator of the Chipstone Foundation/MAM adjunct curator and coordinator of the exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum. "Visitors will have the opportunity to see a huge range of work made during one of the great periods in decorative art." (right: Armchair, 1907. From the hall of the Robert R. Blacker House, Pasadena, California. Designed by Henry Mather Greene (United States, 18701954) and Charles Sumner Greene (United States, 18681957). Made by Peter Hall Manufacturing Co., Pasadena, California. Teak, oak, and leather (replaced), 40 x 24 x 23 7/8 inches (101.6 x 61 x 60.6 cm). LACMA, Museum Acquisition Fund 81.3.3)

The Exhibition

The Arts and Crafts Movement was a response to a century of unprecedented social and economic upheaval. Its name was coined in 1887, when a group of designers met in London to found an organization -- the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society -- for which applied art would be valued as equal to fine art. Many in the movement championed the moral and spiritual uplift that would come with the revival of making objects by hand. The improvement of working conditions, the integration of art into everyday life, the unity of all arts, and an aesthetic resulting from the use of indigenous materials and native traditions also were central to the movement's philosophy.

The Arts and Crafts Movement was an international one -- it touched countries as far apart as Russia and Scotland, the United States, and Australia. The exhibition, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and curated by LACMA's Curator of Decorative Arts Wendy Kaplan, a foremost authority on the subject, focuses on 11 representative countries: England, Scotland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Belgium and the United States. The exhibition explores how the movement's ideals were disseminated and then transformed in response to specific economic, cultural and political conditions.

The exhibition displays masterworks by the best-known designers of the period, including William Morris, M.H. Baillie Scott, Henry Van de Velde, Peter Behrens, Josef Hoffmann, Eliel Saarinen, Gustav Stickley, Greene and Greene, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Art and Industry

For the most part, the Arts and Crafts Movement was neither anti-industrial nor anti-modern. While its adherents idealized the pre-industrial past, they did not reject the present. They believed that machines were necessary but should be used only to relieve the tedium of mindless, repetitive tasks. Britain, at the very epicenter of the Industrial Revolution, was the nation most opposed to the dehumanizing consequences of factory production. Without joy in labor, many English designers felt making goods would have neither merit nor value. At the same time, they felt that objects should be affordable and useful, and therefore, objects such as the exhibition's Small Window Bench, made by the Charles P. Limbert Company in 1907, were produced in factories. The conflict between these two beliefs, and the attempts to reconcile them, comprised the focus of design debates during the first two decades of the 20th century.

Design and National Identity

The use of design to express a country's identity is part of a movement now known as Romantic Nationalism. At the turn of the last century, many politicians, designers, craftspeople and manufacturers sought to establish or reinforce their country's identity by idealizing its past. Romantic Nationalism drew from the British Arts and Crafts, especially the movement's advocacy of indigenous design, traditional ways of making objects, and the use of local materials. For example, in Hungary vernacular embroideries and dress became symbols referents of national identity. In particular, the szur, a richly decorated, woolen overcoat worn by male peasants and shepherds, was widely discussed as an icon of the new consciousness and is represented in the exhibition by an elegant Hungarian coat designed by Júlia Zsolnay in 1905-10.

Art and Life

The concept of completely integrating art and life was fundamental to Arts and Crafts beliefs and was constantly echoed in the movement's organizations and magazines. In the context of architecture and the decorative arts, the building and its furnishings were intended to form an environmental whole, ideally one executed by a single person.

The dream of unity was most fully - albeit briefly - realized in the establishment of utopian art colonies. Four of these are explored in this exhibition: C.R. Ashbee's Guild of the Handicraft in Britain; Darmstadt, Germany; Godollo, Hungary; and the Roycrofters of East Aurora, New York. Each constitutes its own unique paradigm of Arts and Crafts ideals.

Some looked to the Arts and Crafts Movement to provide

a small, still center of handmade work; some for a way to revolutionize

the  production and consumption

of manufactured goods; and others to give material form to national aspirations. The

legacy of the Arts and Crafts Movement can never be definitive, as people

invented the movement that they needed in their particular locale. The

Arts and Crafts Movement embraced progressives and conservatives, proponents

of the handmade and of industrial production, as well as those who believed

that "the service of modern art" must include the revival of traditional

crafts. The movement had to be both modern and anti-modern. These

seeming contradictions were united by the Arts and Crafts Movement's quest

for meaning in a time of radical change by its need to retain a sense of

the individual in an age of mass culture, and by its attempt to make mechanization

and urbanization serve people rather than enslave them.

production and consumption

of manufactured goods; and others to give material form to national aspirations. The

legacy of the Arts and Crafts Movement can never be definitive, as people

invented the movement that they needed in their particular locale. The

Arts and Crafts Movement embraced progressives and conservatives, proponents

of the handmade and of industrial production, as well as those who believed

that "the service of modern art" must include the revival of traditional

crafts. The movement had to be both modern and anti-modern. These

seeming contradictions were united by the Arts and Crafts Movement's quest

for meaning in a time of radical change by its need to retain a sense of

the individual in an age of mass culture, and by its attempt to make mechanization

and urbanization serve people rather than enslave them.

"The movement provided a framework for many essential issues still being debated today," explains curator Wendy Kaplan, "the conflict between standardization and individuality, the question of whether a one-of-a-kind handcrafted object is superior to a mass-produced one, and the problem of defining what kind of design most benefits society." (right: Vase, 1906. Made by Newcomb College Pottery, New Orleans, Louisiana. Decorated by Mazie Teresa Ryan (United States, 18801946). Thrown by Joseph Fortune Meyer (United States, b. Alsace-Lorraine, 18481931). Earthenware, Height: 12 7/8 inches (32.7 cm); diameter: 8 1/8 in. (20.6 cm). LACMA, gift of Max Palevsky M.91.375.31)

Editor's note: RL readers may also enjoy these earlier articles:

and from other web sites:

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional source by visiting the sub-index page for the Milwaukee Art Museum in Resource Library.

Links to sources of information outside of our web site are provided only as referrals for your further consideration. Please use due diligence in judging the quality of information contained in these and all other web sites. Information from linked sources may be inaccurate or out of date. TFAO neither recommends or endorses these referenced organizations. Although TFAO includes links to other web sites, it takes no responsibility for the content or information contained on those other sites, nor exerts any editorial or other control over them. For more information on evaluating web pages see TFAO's General Resources section in Online Resources for Collectors and Students of Art History. Individual pages in this catalogue will be amended as TFAO adds content, corrects errors and reorganizes sections for improved readability. Refreshing or reloading pages enables readers to view the latest updates.

Copyright 2005 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights reserved.